This is a piece that I wrote in 2017. I’m a little amazed at how relevant it is now, three years later.

The CSA Memorial in Front Royal, Virginia

Where’d You Go, Robert E. Lee?

Dona Maria, queen of Portugal from 1777-1815, had a collection of little people. Most were gifts given to her by slave traders or conquistadors. Most were African, though at least one was Brazilian. All were slaves. In 1788, the queen commissioned artist José Conrado Roza to paint a work commemorating the marriage of her two favorite dwarf slaves. Dona Maria dressed the slaves in traditional wedding clothes. She dressed another of her dwarf slaves as a bishop to perform the ceremony. Three African dwarf slaves wear formal clothing and hold musical instruments: a flute, a tambourine. The Brazilian dwarf wears a grass skirt and feather headdress. He points a tiny bow and arrow at the loving couple. Also in the picture is a young boy who is about as tall as the dwarves. He wears only a tiny pair of shorts, leaving most of his skin visible, allowing the viewer to gaze at the pigment condition that afforded him the opportunity later in life to make a living as the sideshow act “Leopard Boy.”

Whether or not the marriage of the queen’s two favorite little people was real is in question. The title of the painting, “La Mascarade Nuptiale,” and the fourteen-year-old bishop suggest that the queen was just playing a game, dressing her slaves like dolls and holding the wedding ceremony as a lark. Roza didn’t title the painting “La Mascarade Nuptiale.” He called it “Portrait des nains de la Reine Marie du Portugal” or “Portrait of the Dwarves of Queen Mary of Portugal.” All we know about the slaves we know because Roza painted their biographies in the hems of their clothing.

Roza’s painting hangs in the Musée du Nouveau Monde in La Rochelle, France. La Rochelle sits on the Atlantic coast, midway between Nantes and Bourdeaux. It’s a beautiful old town. Its harbor and its wealth can be traced back to the seventeenth and eighteenth century slave trade. The Musée du Nouveau Monde shows works that seek to remember the slave trade, to put it context, to examine it unflinchingly.

In May, I presented a paper at an academic conference held at the Musée du Nouveau Monde. Roza’s painting hung in the back of the room. The slaves stared at me, locked in poses seeking to reclaim their dignity, their humanity. They haunted me for the hour-long panel discussion. They set up a residence in my mind and have been living there since I walked out of the museum. They forced me to ask myself questions about global trade, the dehumanization of labor, the mythologies of race and the ways in which these myths justify centuries of oppression. These slaves—according to this mythology—are better off in the court of Dona Maria then they would’ve been in the wilds of Africa or Brazil. They’re lucky. They live in wealth and comfort. At least Dona Maria would’ve rationalized her collection this way, if she ever felt the need to rationalize it. Just as we, in contemporary culture, rationalize the conditions of Foxconn workers by saying that they’re better off than if Foxconn didn’t exist, if they were unemployed and struggling in rural China. As Apple pointed out, Foxconn workers don’t commit suicide at that much higher of a rate than the general population. The nets around the factory are just a precautionary measure.

But when I’m faced with the stares of Dona Maria’s collection of little people, all the rationalizations fall flat. I’m left wondering about my own place as an English professor who travels across a continent and an ocean to present a paper on masculinity in Thomas Pynchon novels. Is my ability to make my living reading books, writing about them, and teaching them predicated on slavery?

I don’t know. I’m not the Dona Maria in this situation. I don’t come at society from a seat of power. Though I have a great deal of empathy for them, I’m not the slaves in this scenario, either. If anything, I’m closest to the painter. It’s my job to document the scene, to try to make meaning of it.

I’ve been thinking about the Musée du Nouveau Monde all summer. In the US, the summer began with New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu removing a Robert E. Lee statue from the city center. It ended with Nazis causing a riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing one and wounding nineteen more anti-racist protestors. The president tacitly supported the Nazis for two days before issuing a disingenuous condemnation, followed by an explicit support of the Nazis. The firestorm was triggered by the proposal to remove another Robert E. Lee statue. The debate about the Civil War monuments is largely framed around the issue of history: are we erasing history by removing these monuments?

This is a naïve question. It treats history as if history is a single document upon which one person with an eraser can demolish something. It ignores that events are frequently lost and found in the retelling of the past. It ignores that history is not some monolithic or objective or definitive thing. History is always political. It is always written. Some aspects are always ignored, others are always privileged. History is always a negotiation about how we want to envision our present, how we represent what we think can be the best of our society, what narratives we want to guide our culture. In his landmark 1973 work Metahistory, Hayden White explained that history always uses the structures and tropes of narratives. White argued that history is primarily told as a romance, a tragedy, a comedy, or a satire. Historians choose the narrative structure to apply to a grouping of historical artifacts. The history itself is not the artifacts—or, if you prefer, facts—it is the narrative that gives meaning to those facts. These narratives are always negotiations of power.

I grew up in Florida in the seventies and eighties. When I learned about Robert E. Lee, the story was tragedy. He was a dashing hero, a brilliant man. As a general, he was far superior to Ulysses S. Grant. Grant was a drunk, a failed president. Lee was a tactical genius who lacked the support of his government, who lacked the war budget of the Union, who lacked the munitions needed to realize his plans. All of his failings could be blamed on someone else. He was also a misrepresented man. He wasn’t a racist. He believed in states and the rights of those states. He was more Virginian than American. He stood up for Virginia, his home and his neighbors.

At least that’s the story I was taught in school. If anyone raised her hand during the teaching of this tale and asked which specific rights the states were fighting for in the war, she’d be sent to the dean for disrupting class. If anyone suggested that the war was about slavery, he’d be corrected. No, we were told, Lincoln didn’t agree to free the slaves until a couple of years into the war. The Civil War wasn’t about slavery. It was a territorial occupation by a hostile government. The Confederates were fighting for their land, their homes. I even had one ninth grade teacher who insisted we refer to the Civil War as the “War of Northern Aggression.”

I left this history behind when I left my backwater hometown. I educated myself in more complex narratives of the Civil War. I forgot about the Robert E. Lee tragedy I was taught in ninth and tenth grade. But another historical monument brought it all back to me. I was in Front Royal, Virginia, looking for a place to eat lunch in downtown when I crossed under the shadow of a monument to the CSA. It took me a second to even figure out what the CSA was and who the armed man at the top of the monument was supposed to represent. Next to this monument was a historical placard that told the story of the Union invasion of Front Royal, the heroes who resisted the brutal Union soldiers, and the battle when Confederate soldiers forced Union soldiers out of the town. The placard claims that the Confederate soldiers were—using language borrowed from George W. Bush’s Iraq War public relations team—greeted as liberators.

As I read the placard and looked at the statue, I became hyperaware of my whiteness. I watched a woman with all the socioeconomic signs of someone who was poor and who had skin that I’ve been taught to see as black walk into the courthouse. I wondered if she was going inside for her own court case. The outfit that looked like her Sunday best and the battered manila folder in her hand seemed to suggest so. And I wondered what it would be like be a poor black woman who has to walk past this Confederate soldier monument and this placard that portrays the war as a War of Northern Aggression on her way to court. How must she feel about her chances once she gets inside?

Knowing nothing about this woman, whether she was an employee at the courthouse, an attorney, or a defendant, I wanted to add a statue of her to the courthouse lawn. Maybe, if I was feeling preachy, I’d add a simple inscription. “With no liberators to save her from the institutional racism of her town, she still got out of bed and faced the day.”

The racism of the Confederacy shouldn’t be something that is earnestly debated. Of course a government formed to enslave a group of people based upon their race is racist. Of course the people who fought for that government are racist. There is more to it. People did have to fight for their homes. United States soldiers did commit atrocities. Some citizens probably did celebrate the arrival of Confederate generals like Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. But on top of all that, the war was an attempt to enslave a giant group of Americans based on their perceived race.

Even if we take the supporters of the monuments for Lee and the Confederacy at their word—that we need to honor soldiers who fought against an invading force for their homeland, that we need to remember General Lee as a powerful general and a brilliant tactician—there’s something very troubling about the narratives these monuments tell. For the monuments to the soldiers, we’re defining heroism as a willingness to obey your superiors unquestioningly and a willingness to fight regardless of the morality of the battle your superiors are fighting. For the monument of Lee, we’re defining a strong, authoritarian leader who rose to power as part of a military coup as a hero. These are the values of a totalitarian regime, not a democratic state.

“La Mascarade Nuptiale” by Jose Conrado Roza. (Sorry about the corona of light in the corner. It was unavoidable.)

I know that Civil War monuments aren’t the only troubling representations of history. The California town I live in has a statue of Junipero Sera in front of City Hall. For whatever good Sera may have done (the Pope just made him a saint), the defining act of his mission building along the coast has to be his enslavement and brutal treatment of Native Americans. Most California missions are surrounded by the mass graves of the slaves killed during the construction of the missions. Farther up the coast of California sits the Hearst Castle, a state park and monument to a man whose newspaper empire was the first step in the long deterioration of a free media in the United States, who fabricated an international incident to catalyze two unjust wars, who destroyed Orson Welles’ career just because Welles made fun of Hearst’s mistress, and who unequivocally supported McCarthyism. And what did he get for all his crimes? Why, this beautiful mansion in one of the most beautiful spots in the world.

The list of problematic monuments goes on and on. In one of his responses to the riots in Charlottesville, Trump pointed out that George Washington was a slaveholder, as was Thomas Jefferson. He asked if we should go after monuments to our founding fathers as well. Trump didn’t ask this question in earnest, but maybe we should. Maybe he’s tapped into the heart of the problem, which is that we know our history has been written to favor people whose actions are reprehensible, but we don’t know how to fix that. Maybe, to take one step in the right direction, we shouldn’t tell the story of Jefferson’s sexual relationship with a slave as a great romance. Instead maybe we should start the story by asking some very basic questions like, can a sexual relationship really be consensual when one participant sees the other as his property? And, if it can’t be consensual, isn’t that rape? And maybe she did love him, but wasn’t she essentially a kidnap victim (weren’t all slaves?), so wouldn’t any love she might have had been more akin to Stockholm Syndrome? Finally, if we asked these questions, would we have a fundamentally different relationship with people in power?

What impressed me most about the Musée du Nouveau Monde was its ability to raise difficult questions without pretending to know the answers. It raised questions in one particularly special way: the city of La Rochelle purchased the house of an old slave trader. That house is now the museum. As you walk through the spoils of slavery—the opulent home in the beautiful harbor city—you see art that forces you to reckon with the dehumanizing acts that comprised slavery. What if we did that here? What if Hearst Castle wasn’t full the wealth Hearst hoarded and instead was full of the art of the lives he destroyed? What if, instead of taking down statues to Robert E. Lee, we instead added statues of former slaves chipping away at Lee’s pedestal?

Or maybe not we could do something that’s more quietly radical. My favorite monument is just outside the San Luis Obispo train station. It’s a statue of two gandy dancers building the railroad tracks. Their hair, posture, the very wrinkles of their clothes show them working hard. One wears a hat. Both have long braids. They’re both recognizably Chinese, but nothing about their features is exaggerated or caricatured. They look like real people, like the sculptor used a real photograph (which would’ve been impossible) or real models. It sits in the middle of a traffic circle. Seen from one side, the workers are flanked by a train station and the tracks they built. Seen from the other side, the workers stand between buildings that are more than a century old, that were once the inns and restaurants and boarding houses of workers and travelers. There’s no indication about the working conditions of the gandy dancers, about whether or not they could stay at the inns or the boarding houses, about what happened to them once the railroads were built or during a twentieth century that was long and unfriendly for Asian Americans. All of that you have to learn on their own. That’s okay. At least the workers are here, visible again.

Have you ever watched The Big Lebowski and wondered to yourself, where does the Dude fit in the spectrum of constructed masculinity from Philip Marlowe to Doc Sportello? Have you ever wished there were a Pynchon scholar who could explain to you the ways in which writers rewrite famous texts, and how they revise them? Have you ever wished someone would really explain the specifics of how our culture teaches males to act like men? If so, you’re in luck. I just did all that.

Have you ever watched The Big Lebowski and wondered to yourself, where does the Dude fit in the spectrum of constructed masculinity from Philip Marlowe to Doc Sportello? Have you ever wished there were a Pynchon scholar who could explain to you the ways in which writers rewrite famous texts, and how they revise them? Have you ever wished someone would really explain the specifics of how our culture teaches males to act like men? If so, you’re in luck. I just did all that. Three incidents in my life had become linked in my head. I felt like they were connected, but I couldn’t explain why. Whenever I talked about it, I ended up rambling. At the same time, the editor at Morpheus asked me if I’d written anything recently he could use. So I sat down and wrote an essay that allowed me to clear my head, articulate my thoughts, and get something over to the editor. I’m pretty pleased with how it came out. You can read it

Three incidents in my life had become linked in my head. I felt like they were connected, but I couldn’t explain why. Whenever I talked about it, I ended up rambling. At the same time, the editor at Morpheus asked me if I’d written anything recently he could use. So I sat down and wrote an essay that allowed me to clear my head, articulate my thoughts, and get something over to the editor. I’m pretty pleased with how it came out. You can read it  My university has a running column in the Ventura County Star on Sundays. Our public relations person asked me to contribute a column recommending books for the summer. She also wanted me to make it newsy. So I did what everyone in the news is doing. I started with Donald Trump. This was my original first paragraph:

My university has a running column in the Ventura County Star on Sundays. Our public relations person asked me to contribute a column recommending books for the summer. She also wanted me to make it newsy. So I did what everyone in the news is doing. I started with Donald Trump. This was my original first paragraph:

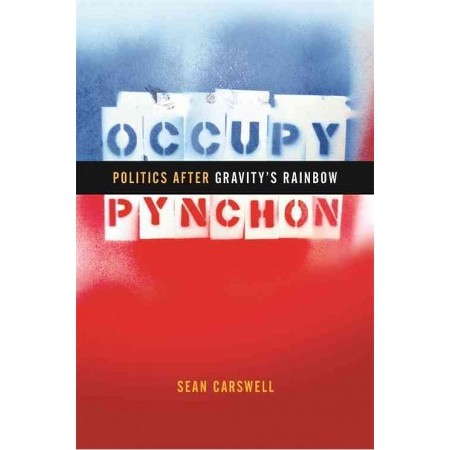

For the past several years, I’ve been working on a book about politics in Thomas Pynchon novels. It’s been a hell of an undertaking. I’ve reread all of Pynchon’s works several times. I’ve read hundreds of books and academic articles about Pynchon’s novels. I’ve studied economic and political and literary theory. I’ve written several drafts of a book, published a few chapters in peer-reviewed journals, found a publisher, and finished one round of edits. The book is under contract right now with the University of Georgia Press. It should come out sometime next year.

For the past several years, I’ve been working on a book about politics in Thomas Pynchon novels. It’s been a hell of an undertaking. I’ve reread all of Pynchon’s works several times. I’ve read hundreds of books and academic articles about Pynchon’s novels. I’ve studied economic and political and literary theory. I’ve written several drafts of a book, published a few chapters in peer-reviewed journals, found a publisher, and finished one round of edits. The book is under contract right now with the University of Georgia Press. It should come out sometime next year.